Conflict Till The Last Trump

You can learn many things from watching a presidential race, not all of them political.

The combination of high stakes and detailed media coverage surrounding the Republican race to the nomination, for example, allows you to view everyday office and workplace dynamics through the lens of a high-profile struggle that everyone can identify with.

In one corner, we have a number of relatively “traditional” Republican presidential contenders. They serve the role of the “usual players” in any organization. These people guard the status quo and tend to traditionally staff the middle to senior management ranks. Top ranks and C-level positions are normally selected from a competing field of these players, for good or ill.

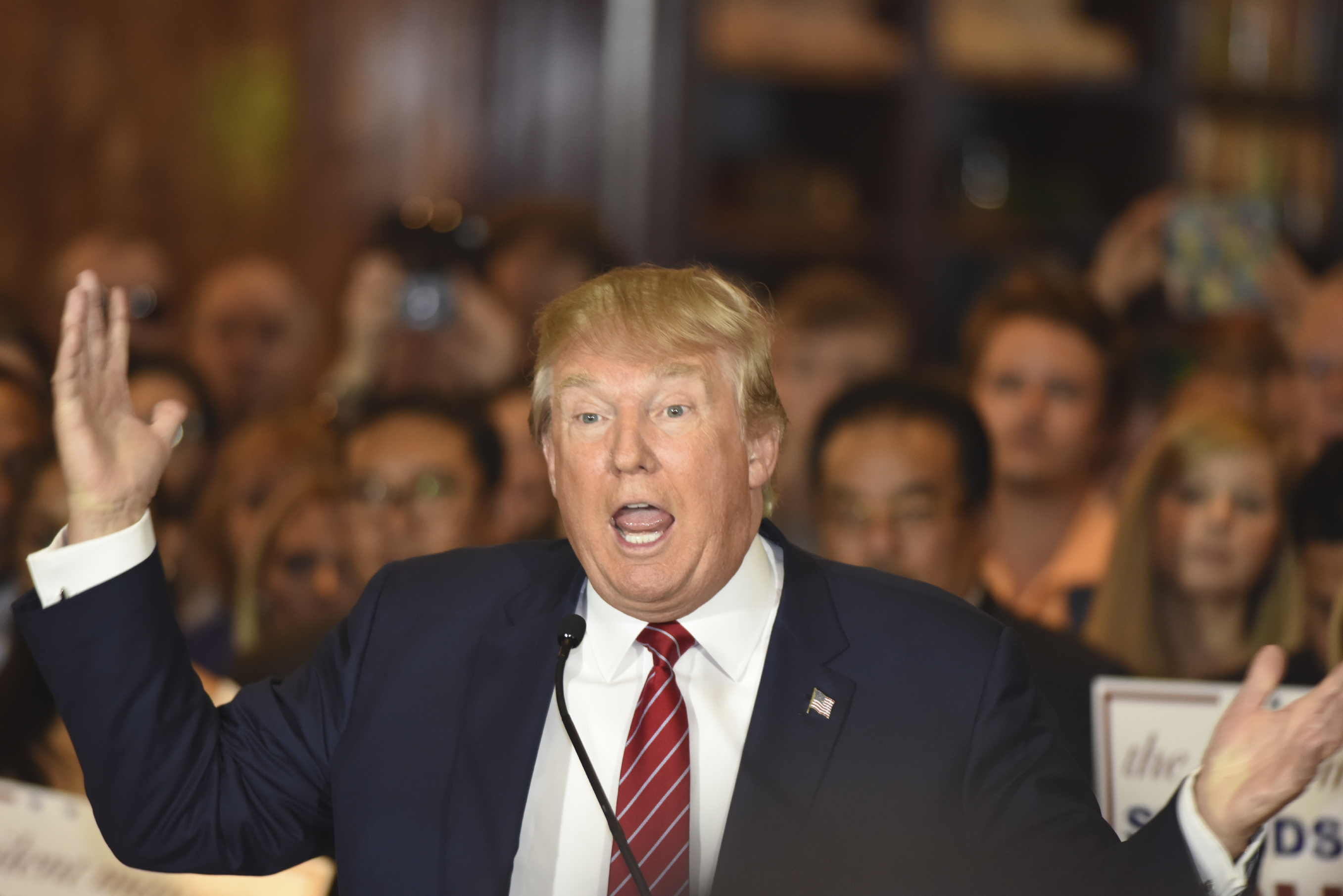

In the opposing corner, we of course have Donald Trump. Setting his politics entirely to one side, Trump represents the new and disruptive force of change. When disruptive forces hit established organizational structures, there is usually very little warning, and certainly the established players almost never see the signs. It could be a new person, as with Trump, or a change in industry practice, consumer habits, government policy or a wide range of other things. The disruptive force arrives like a miniature tornado, knocking over the furniture, upsetting well-established norms, angering some people, delighting others and throwing still others into uncertainty and doubt.

Work teams, like all living systems, react to threats in a way that is fairly predictable to people who study such things. Those whose hope for benefit from a change in the game – or even from throwing the game board away – exceeds their perceived benefit from playing the old game are usually enthusiastic supporters of disruptive change. There are certainly a great number of these supporting Donald Trump. The war-cry of this tribe sounds like “Anything would be better than what we have!”

Then there are those who are doing well within the status quo. For them, their present roles, survival and benefits are good and also very well-defined. In the Republican presidential race, this of course is the Party itself and its established leaders and candidates. A disruptive change may help them or hurt them – most often it will hurt – but the key point for them is not the possible benefit of change but the uncertainly it brings. Their war-cry is something like “Whoa, bad idea, not so fast!”

Italian strategist Niccolo Machiavelli thought that the forces of conservatism would always be greater than the force for disruptive change, because those who stand to lose are certain they will lose, while those who hope to benefit are merely hoping, and therefore make lukewarm supporters. As anyone who works in a large organization can tell you, Machiavelli is right most of the time. But as the history of revolutions, strikes, political upsets and industrial disputation will tell you, sometimes the hope for change from chaos is so great that it overcomes the establishment’s fear of loss. That’s when you get very surprising CEO appointments, expected candidates not getting the jobs they were expected to get, and possibly – just possibly – a history-making upset in the Republican party.

Although the candidates would like to think of themselves as independent-minded people who are choosing their own path, as do both traditional leaders and disruptors at your workplace, when seen from a sufficiently elevated perspective they are actually pieces on a game board. Folks who study team and leadership dynamics in a scientific way play out and simulate “serious games” like this all the time. There’s a limited number of choices available to each player, and therefore a limited number of possible choices for game play. Each of these has its own –probably different – payoff for, say, you, as a voter or as a member somewhere in a workplace team structure. Usually the variables are so complicated that all you can do is simulate the outcomes and make decisions based on the odds.

As a voter or as a person in a workplace team watching the titans battle far above you, you, too, have only a limited number of choices. You can engage and choose a winner, engage and try a more nuanced support strategy, or disengage. Most people in a team will select the first or last of these choices.

If you bet on an uncertain winner and win, then you can start waiting for the expected benefits – and you may be right or wrong in that expectation. If you disengage, you increase your certainty of safety from bad personal consequences but still have the uncertainly of being affected by the eventual outcome. And if you try to stay engaged but balanced, not committing until and unless you have to, you’re trading certainty against payoff. Increasing one reduces the other, to the extent that the real outcome affects you.

For the individual Republican candidates, none of this helps much, because they are probably only going to get one shot at playing the game – one “round”, as we team simulators say. For them, that makes it a crap shoot.

But for the Republican Party, and for you at work, you will play many rounds of this “game”. You and the Party are in it for the long haul. Because of that, you CAN use gaming and simulation to maximize your odds of a good result, just as the Republican power brokers are doing right now in a war room.

What’s your own situation at work? Is it changes in the senior management? A new supervisor? A change in your industry? Budget cuts? A new project you want to be on? Whatever it is, game out the decisions in a simple diagram. Be sure to consider not just the payoff to you for each consequence but the likelihood of that consequence. It’s that second step that people usually miss, unless they really game it out and then simulate a few rounds of possible outcomes.

For most of us at work, someone else designs the game, just as the candidates don’t choose the debate formats or the primary voting rules – much to their frustration. For most of us, the game pieces are also decided by others, and the player we get to be – and the rules we must follow – are also assigned to us. With these things set outside our control, it’s easy to feel powerless, to give up, or to make impulsive choices in hopes of a random stab at good outcomes.

But in fact the quality of game you play, and the strategies you research, simulate and choose, are entirely up to you.

Engage us on Facebook

Follow us on Twitter

Tweets by @mymcmedia