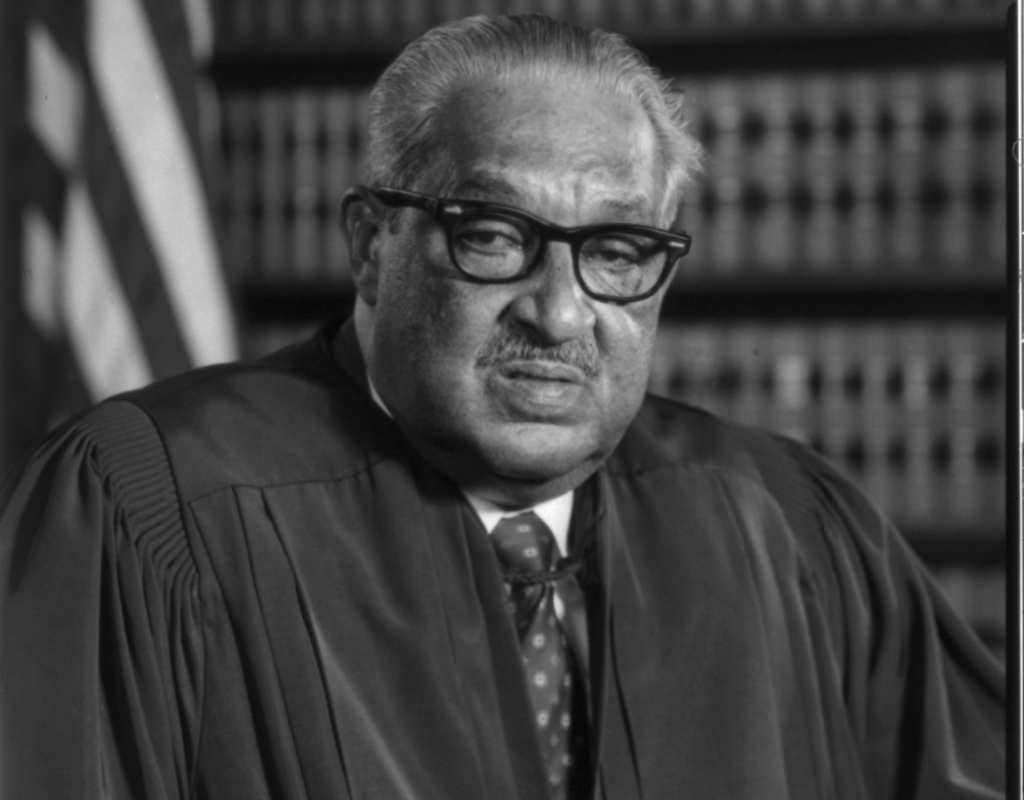

Black History Month: MCM Spotlights Justice Thurgood Marshall’s Rockville Roots

Originally published on Feb. 10, 2020

U.S. Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall’s work to integrate schools began in Rockville, where he argued for equal pay for black teachers in the now-vacant grey courthouse at Courthouse Square in Rockville.

“It was here, in some ways, that he started the quest,” said Ralph Buglass, a speaker with the Montgomery County Historical Society. “It’s terribly significant that here in Montgomery County, he really started the effort to stop segregation.”

Before Brown v the Board of Education integrated American schools, the law of the land was separate but equal so there were schools here that taught only whites and schools that taught only blacks.

Marshall, who went on to become the first African American on the U.S. Supreme Court, took on the case of William B. Gibbs Jr., a teacher at the Rockville Colored School, which was located at Beall Avenue and North Washington Street, behind what is now Dawson’s Market.

Back in 1937, Gibbs was making $612 a year, while white teachers with the same education received $1,176 a year, which was “almost double,” Buglass said.

Even white janitors were paid more than African Americans who taught in the colored schools, Buglass said.

Marshall, who lived in Baltimore and got his law degree from Howard University in 1933, never lived in Montgomery County. But the case intrigued him, according to Buglass, because Marshall saw it as a way toward achieving total integration in education.

He dreamed of a world where black children had the same educational materials and volumes of books that white students already had.

Marshall argued Gibb’s case before a board of judges. Instead of arguing against the current law of separate but equal, Marshall cited the 14th Amendment, which said all American citizens are equal.

The judges ruled unanimously that the case should go forward, and the matter was soon settled out of court, with the board of education agreeing to raise Gibbs’ salary to what white teachers make over a two-year period.

Marshall continued his fight for civil rights throughout Maryland and the entire country and eventually led the successful charge in Brown v Board of Education. As a result, American schools were integrated.

Montgomery County went on to become the first county in Maryland to completely end school desegregation, although that didn’t happen until 1961.

However, education for black students began improving in the 1950s when more modern elementary schools were built for them that were “generally on a par with white schools,” Buglass said.

A marker commemorating the Gibbs case currently sits in front of the vacant Rockville courthouse, but Buglass said the historical society is “working to get a better marker there.”

He explained, “To me, it’s just a remarkable story, right here in Montgomery County, to argue this case.”

Marshall’s work with Gibbs “is considered the very first victory in segregation in kindergarten through twelfth grade public education,” Buglass said, adding, “That was his only appearance here in Rockville.”

The William B. Gibbs Jr Elementary School in Germantown was named in Gibbs’ honor.

Marshall lived from July 2, 1908 to January 24, 1993. He was appointed to the U.S. Supreme Court in 1967. Following his nomination by Pres. Lyndon Baines Johnson, Marshall faced stiff opposition from some members of both political parties. He went on to be confirmed by a vote of 69 to 11.

“By and large, Thurgood Marshall was known for his civil rights work, thus earning him the name ‘Mr. Civil Rights,’” Buglass said, noting there was a movie documentary on Marshall bearing that title.

In that documentary, U.S. Supreme Court Justice Elena Kagan, who clerked for Marshall, called Brown v. Board of Education historic. “I don’t know of a legal decision in this country that was greater,” she said in the documentary.

Marshall went on to fight for the underdog throughout his lengthy judicial career.

And he spoke with the conviction of someone who knew injustice. Even Marshall was deemed unfit for all-white schools. He attended law school at Howard University when the University of Maryland did not accept colored students.

Engage us on Facebook

Follow us on Twitter

Tweets by @mymcmedia