A Homeless Woman’s Death Becomes ‘Call to Action’

Before the mental illness took over, Kathleen Garlington was a professional pianist. But as she became more paranoid, she lived on the streets, often in Kentlands.

“She was an incredibly intelligent woman,” said Sherry Moitoza, director of social concerns at St. Rose of Lima Catholic Parish in Gaithersburg. “When you’d have a conversation with her, when she was in a sane mode, it would be an incredibly deep, and then she could switch like that.”

In December, the county declared Kathleen, 61, as “a chronically homeless person,” Moitoza said. The designation meant service agencies could begin the process of getting her off the street.

Because of her illness, Garlington refused to sign paperwork that could lead to help. She feared that the papers would help someone steal her identity, Moitoza said.

On March 13, Montgomery County was only a few days away from finding her a home. The plan was to put Garlington up in a hotel while more permanent plans were drawn up. Moitoza and others who cared for Garlington searched for her all through Kentlands — where the woman spent most of her time.

That evening, Garlington’s body was found in a stairwell behind a shop that led to upstairs apartments. Although Gaithersburg Police did not suspect foul play, protocol called for an autopsy. Her sister, Monica Garlington, said the results showed she died from complications of high-blood pressure.

Garlington had adopted St. Rose of Lima. She never asked for money or food, Moitoza said. She occasionally would request a book, or to use the microwave to heat up coffee. Sometimes she’d be in the chapel napping, startling whoever arrived early or locked up for the night.

“She was an intriguing person because there was something that endeared you to her,” Moitoza said. “You would love her, and you would hate her. You would end a wonderful conversation with a yelling and screaming match.”

On April 3, the church hosted her funeral.

Monica Garlington said it was a beautiful service. The sermon, from Father Agustin Mateo Ayala, centered on the homeless and mental illness. He said we should not forget who they were before they were afflicted with homelessness or disease, Monica recalled.

In the pews were people Kathleen knew and members of the Montgomery County Coalition for the Homeless, who asked if they could come. Monica said she would be upset if they didn’t.

Kathleen’s story was the subject of April 17 testimony before the Gaithersburg Mayor and Council.

“It was a funeral I wish had never happened, a story of a life I wish didn’t end the way that it did,” said Jen Schiller, chief programs officer for MCCH. “But in this story lies a new call to action.”

She thanked the city for recognizing homelessness is unacceptable, and its funding to homeless programs.

Although the community paid its respects to Kathleen, Monica said they only knew one part of her.

“Everybody in the church knew Kathleen after she had a mental illness. They didn’t know her from before,” Monica said. “They didn’t know all this stuff and Kathleen wouldn’t share it all.”

Kathleen was the oldest of six children. Raised in Michigan, she began playing the piano at 12, according to her obituary. She had come to Washington, D.C., to study, at Catholic University and at George Washington University, learning piano accompaniment for vocalists and instrumentalists. Monica said she played at Mass for many years.

About 15 years ago, their parents took ill, and Kathleen moved back to Michigan to care for them. They died about five years ago, two weeks apart, and it fell to Kathleen’s shoulders to sell the belongings and the family home, Monica said.

“I think it was too much for her,” Monica said. The isolation seemed to make her more paranoid.

She lived in motels for a while, until her money ran out, Monica said. Then she lived with a sister in Baltimore and Monica in Florida.

A couple of times, Kathleen was charged with trespassing at a post office. The family hoped, Monica said, that the charges would help get her admitted to a hospital. It turned out, the standard for hospital admission is much more difficult, she said.

“The thing that haunts me is that somebody that’s paranoid and not rational, is someone who can say, ‘I’m not a danger to myself or others,’ and that’s better than someone who’s rational and says you need to get better,” Monica said.

About four years ago, Kathleen started living on the street.

“On the street, she was in that kind of heightened state of paranoia-anxiety. She was very vulnerable,” Monica said.

“As long as Kathleen wouldn’t take medication, we couldn’t bring certain things to fruition,” she said.

From Florida, Monica would call shelters and then try to get Kathleen to go to one. Because of her paranoia, she refused to go. Or she’d decide to go at 10 p.m., and the shelter would be closed for the night, Monica said.

“It makes it even more sad because this process took so long. It was a combination of a lot of things. Who knows if she would have ever accepted [housing] or been able to survive as someone who is paranoid? But we were so close,” Moitoza said.

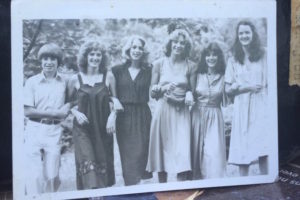

Monica Garlington supplied the photos below. They include images of Kathleen with dogs — including one in her crib. One also illustrates her love of music dates back to a young age.

Engage us on Facebook

Follow us on Twitter

Tweets by @mymcmedia